Improving Cattle Production Through Forage Nutritional Contributions

This article was originally published February 2010 on Page A14 in the Prairie Posts™ Bullbreeders 2010.

Cattle are expected to have the highest average daily gain in the early portion of the grazing season (June-July) but do not usually maintain the same average daily gain throughout the grazing season. Why is that?

A couple of reasons may be at play: 1) the age of the stand and 2) the species within the pasture.

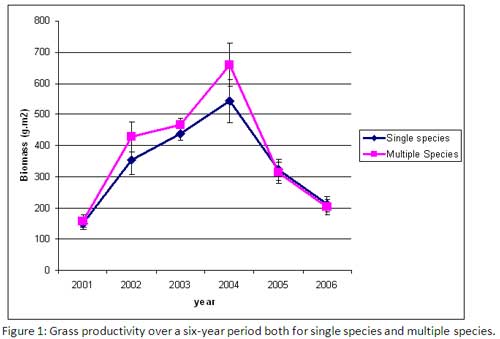

At the Semiarid Prairie Agricultural Research Centre (SPARC), we have noted that a decline in biomass production occurs four to five years after seeding. This is in part due to the plants having captured all readily available soil moisture and nutrients. A greater amount of biomass was obtained with mixtures at SPARC, but the decline still occurred. With less biomass production, the more time the animal spends looking for forage and less weight gain. The pasture needs to be rejuvenated or reseeded to return to the high production and nutritional quality of a younger stand.

Age of the plant is a contributing factor to nutritional quality, but another factor is the species of plant itself. A large majority of pastures are single species seedings that mature in a narrow time span, thus reaching their full nutritional potential also in a narrow time span. Different species mature during a growing season at different rates and times within the growing season. For example, crested wheatgrass is considered a spring grass because it matures early and reaches its nutritional peak just before flowering, whereas western wheatgrass matures later and reaches its nutritional peak in southwest Saskatchewan later in July. This difference in nutritional value is not just found within species of grasses but also among plant types (grasses, forbs, shrubs). Generally, grasses hold their energy value best as they mature, with forbs such as alfalfa next best and shrubs the least. The tables are turned for digestible protein, with shrubs retaining protein the best, forbs again next and grasses losing their digestible protein most rapidly as they mature.

With different maturing times and different abilities to retain nutritional value, one would expect pastures containing appropriate mixes of species to provide nutritional stability throughout the grazing season. At SPARC, we have found that adding a legume to a grass stand can sustain average daily gain in the late summer period. Work with diverse mixtures of grasses, cool-season and warm-season grasses also has demonstrated the possibility to maintain average daily gain. Work with different plant types at SPARC has identified shrubs retaining adequate crude protein values for cattle maintenance in the fall when many grasses are deficient.

Cattle average daily gains can be maintained if stands are kept in their most productive state. This state can be influenced by the age, plant species and type of plant present, all of which can be managed for improved livestock production.

Michael Schellenberg, PhD, PAg, CPRM

Range and forage plant ecologist

Semiarid Prairie Agricultural Research Centre

Swift Current, SK